Ah, the good old days, when entertainment meant for children thought nothing of making a cartoon based solely off a piece of classical music over five minutes long. What an interesting concept. It certainly wouldn't work these days, but ah well. What can you do? I will say, though, that I have a feeling that Franz Liszt (yes! I've finally done the post I've been promising for the past month) would not have objected too strenuously to the over-the-top performance done here by Messrs. Tom and Jerry.

|

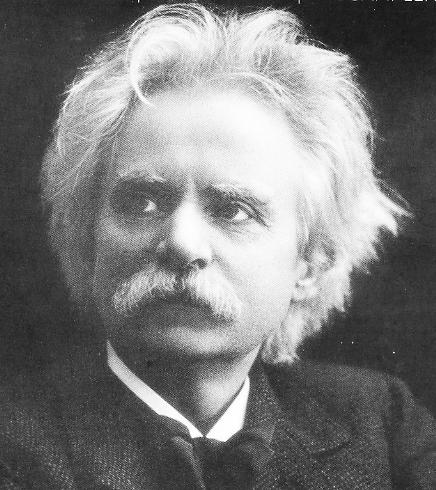

| With that brooding stare, you'd want his gloves too. Don't lie. |

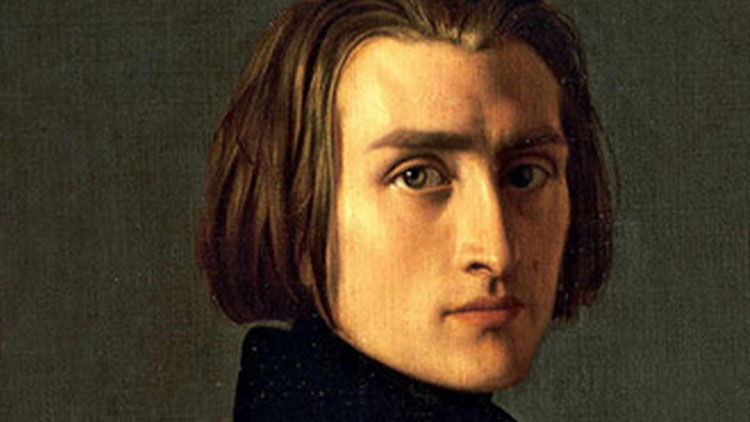

Liszt married rather young and had three children with his first wife in rapid succession. His daughter, Cosima, became rather well known for, y'know, marrying Richard Wagner and starting the Bayreuth festival. (It's truly fascinating how tight-knit the musical world can be sometimes, isn't it?) In the 1840s, Franz took up a touring life to support his growing family, and to say that it was a success is to put it far too mildly. Liszt was a phenomenon - of the likes of Elvis. Women (and, I'm sure, at least a few men) went absolutely wild over his performances, and would grapple for souvenirs of silk gloves and handkerchiefs. He was so successful that he was able to retire from concert life at the age of 35, not only financially set for life but able to quit at the top of his game, so to speak. He moved to Weimar and stayed there for quite some time, but the death of two of his children and a failed romance sent Liszt to Rome, where he lived in solitude for several years. For the last ten years of his life, Liszt split his time between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, composing and giving master classes. He died at Bayreuth in 1886, during the festival his daughter started.

|

| Though he probably should've bit the bullet and cut his hair later in life... |

Though Liszt is known mostly for his piano music, it must not be forgotten that he was also the inventor of the symphonic poem, a genre of music without which 2001: A Space Odyssey would be decidedly less epic. However, since Hungarian Rhapsody #2 is indeed a piece of piano music (or at least was originally a piece of piano music), it is there we shall stay. Because Liszt was Hungarian, it only followed that he was strongly influenced by Romani music and made use of the Gypsy scale. This scale is formed by taking an A minor scale (A B C D E F G) and raising the fourth note of it, giving A B C D# E F G. This can clearly be used in any key - the Hungarian Rhapsody is in C# Minor - but for the sake of not having a million #s, A minor is the easiest to see.

The Rhapsody itself was composed in 1847 and published in 1851 as part of a set of 19. Originally arranged as a piano solo, the overwhelming popularity of the pieces gave Liszt the opportunity to arrange it first for piano and orchestra and then for piano duet. It became part of the standard piano recital repertoire very quickly, and for a time, almost every recital ended with the piece due to its outstanding virtuosity. This near-ubiquity gave companies like Warner Brothers and Hanna-Barbera the license to use the piece all over the place; apart from the Tom and Jerry cartoon, there is a Bugs Bunny short, a few Disney cartoons, and even a song in Animaniacs. I can't say that this would be the first piece of music I would personally pick to become the unofficial cartoon anthem, but it seems to have worked for the past 75 years or so. Go figure.

Further listening:

Like Liszt, and also Mozart? Try Reminiscences de Don Juan, performed by Valentina Lisitsa: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xSZ860AbOw

Like Liszt, and also having lots of feelings? Try Liebestraum no. 3, performed by Daniel Barenboim: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y4XEPdYO5mM&feature=related

And in honor of the beginning of school years across the world (but mostly Vassar's), here's his Gaudeamus igitur paraphrase: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0s4zCFSLcw

And finally, for creepiness' sake, a cast made of his hands: