The piece in question today can be found at around 4:10, though the entire cartoon is wonderful (and a particularly good parody of Fantasia, if I do say so myself). The melody of "On the Beautiful Blue Danube" is perfectly suited to the cartoon world, and - if I may be so bold - I don't think that Johann Strauss II would mind that. Strauss did not seem to have dreams of bold artistic statements, but instead was content writing popular music that got people up and dancing. A 19th-century Katy Perry (or Dr. Luke, for consistency's sake) to Richard Wagner's Radiohead, to complete the too-far-gone metaphor.

|

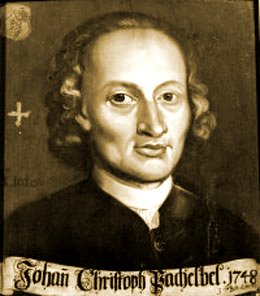

| Distressingly, not the largest his mustache ever was. |

Things were looking up for a while, until the Revolution of 1848, in which Johann (being a Twenty-Something Who Wants to Change the World) took the side of the revolutionaries. Papa Strauss was staunchly pro-monarchy, and the monarchs took a long time to fall in love with Strauss Jr. (an honorary title created for Johann Sr. was denied from his son for over twenty years after Sr.'s death, to name just one indignity). Johann Sr. died in 1849, at which point Jr. was finally able to assert his place in Viennese musical culture; and assert himself he did.

Some composers, like Beethoven, Schoenberg, and Wagner, look for new ways to express large artistic ideas, and the works they created stand testament to their forward-thinking artistic vision. Not so with Strauss. He wrote - for the most part - dance music. And he did it very well. Upon making a name for himself, he enjoyed a near-constant level of success that lasted the rest of his life. He toured in Russia and the United States, and was also well-liked by composers of his day. Richard Wagner himself mentioned that he enjoyed his waltzes, and Richard Strauss (no relation, of course) paid homage to him in several waltzes composed for his opera Rosenkavalier. Of course, Strauss did not simply write waltzes and other dance-hall music; he also composed several operettas (in a nutshell: shorter, decidedly less serious operas). Though these are not well-known today, I hold that Rodgers and Hammerstein got a lot of inspiration from them (seriously: there are pieces in Der Zigeunerbaron that sound like Carousel or The Sound of Music, just in German). Strauss died in 1899 at 73, after a very successful - if not ground-breaking - career, a well-loved composer.

|

| If done correctly, your waltz should be clearly outlined. |

The "Blue Danube" waltz (or, as it is wordily-known in German, An der schönen blauen Donau) was composed in 1866 and premiered the next February. It was not a runaway hit at first, and during the revision process, words were added (and then subtracted). Finally, at the 1867 World's Fair, it was premiered in its finalized form to great acclaim. To call it a single waltz is a bit of a misnomer; it is really a collection of ten small, thematically similar waltzes strung together. However, as a whole, it proved to be extraordinarily successful. It has become somewhat of an unofficial national anthem for Austria, and was used quite notably in the docking scene in - of course - 2001: A Space Odyssey, which also featured Mr. Richard Strauss's Also Sprach Zarathustra. For someone who never purported to be making art music, Johann Strauss sure rubbed shoulders with the greats. If there's a moral here, it's that not every artist has to be preoccupied with High Art - there's quite a lot of dignity in the enjoyable. There's room for the Katy Perrys of the world right up with the Radioheads, and I think that's a most excellent thing.

Further Listening:

Don't believe me that Strauss operetta could be Rodgers and Hammerstein in German? Try "Wer uns getraut..." from Der Zigeunerbaron, performed by Carmen Monarcha and Morschi Franz: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-_F2D486k8&feature=related

Want to see what the 'high-art' form of the waltz became? Try "Valse Brilliant #1" by Chopin, performed by Lang Lang: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=viHg_kIWUeI

Interested in hearing how Beethoven paid the bills? Try Contredanses 3-7 (and check out the original theme from the Eroica symphony at 1:35!) performed by the Russian National Orchestra: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WfWyXW6ETlI